December 2017

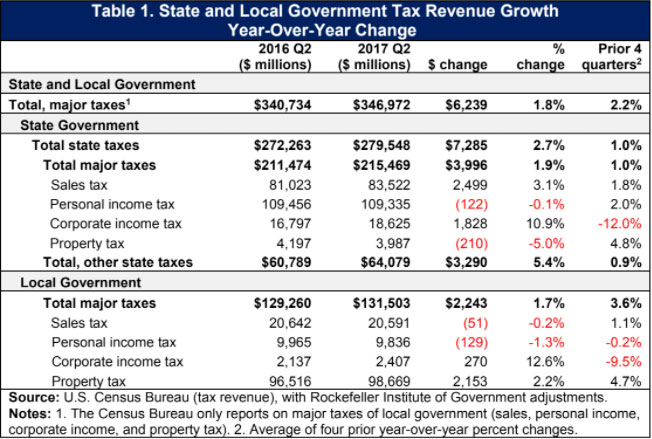

State and local government tax revenues grew modestly in the second quarter of 2017, although revenues from state and local personal income taxes declined and continued to show significant swings from one quarter to the next. State sales taxes and corporate income taxes also increased in the second quarter, as did state motor fuel taxes, but state sales tax revenues still lagged behind rates of increases in previous economic expansions. Finally, local government property taxes grew, though their rate of growth slowed from recent trends.

Specific findings include the following:

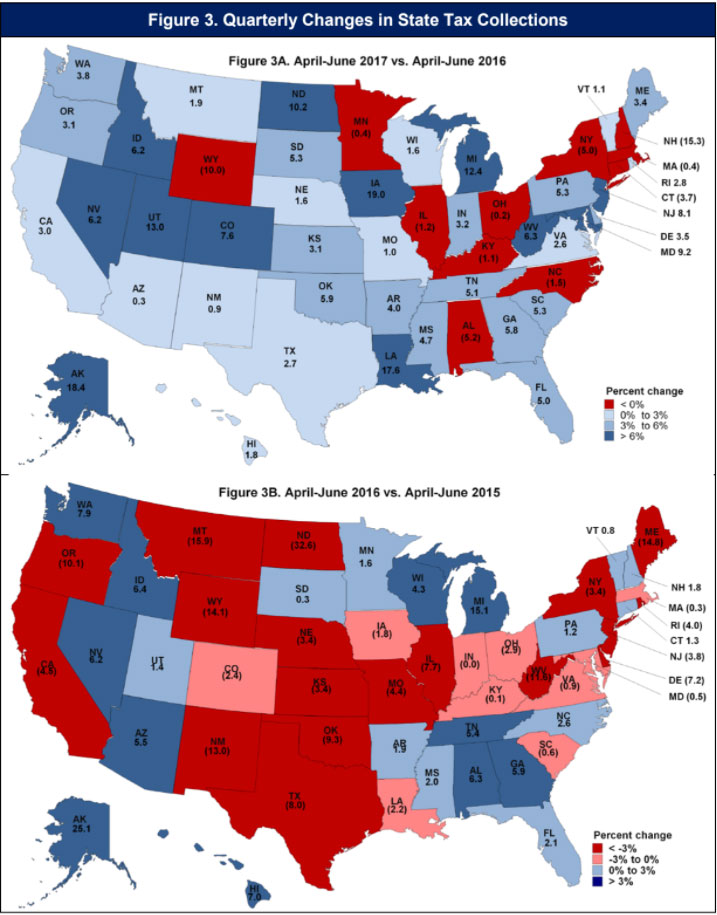

State tax collections continued to show large regional differences. Most of the states west of the Mississippi reported revenue growth in the second quarter of 2017, while states east of the river were more likely to have experienced declines—a pattern we also saw in the first quarter. Yet there was an important change; fewer states saw revenue declines. Only 11 states reported decreased revenues in the second quarter of 2017, a large drop from the fourth quarter of 2016, when 19 states reported declines, and an even larger decline from the widespread decreases in the second quarter of 2016, when 28 states experienced reductions. Finally, the Institute has closely monitored estimated and final payments for income taxes, and these data show declines in both types of payments for the second quarter of 2017.

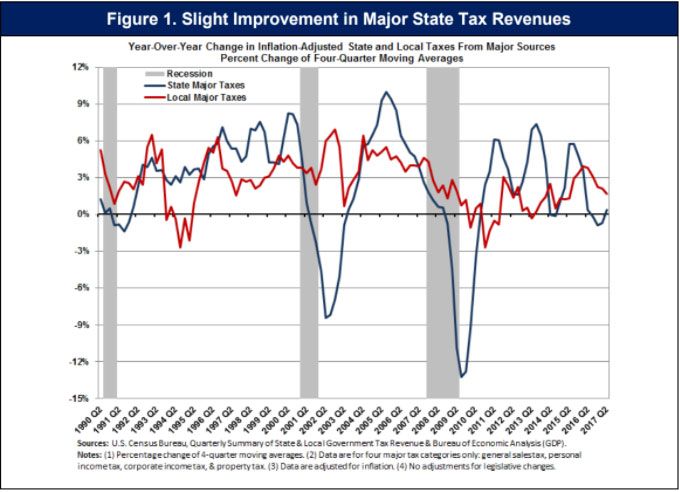

State and local tax revenues fluctuated wildly over the last four years, despite the long and fairly steady economic recovery since the last recession.

Figure 1 shows changes in major state and local tax revenues since 1990. The graph displays year-over-year percentage changes in the four-quarter moving average of inflation-adjusted state and local tax revenues from major sources—personal income, corporate income, sales, and property taxes.

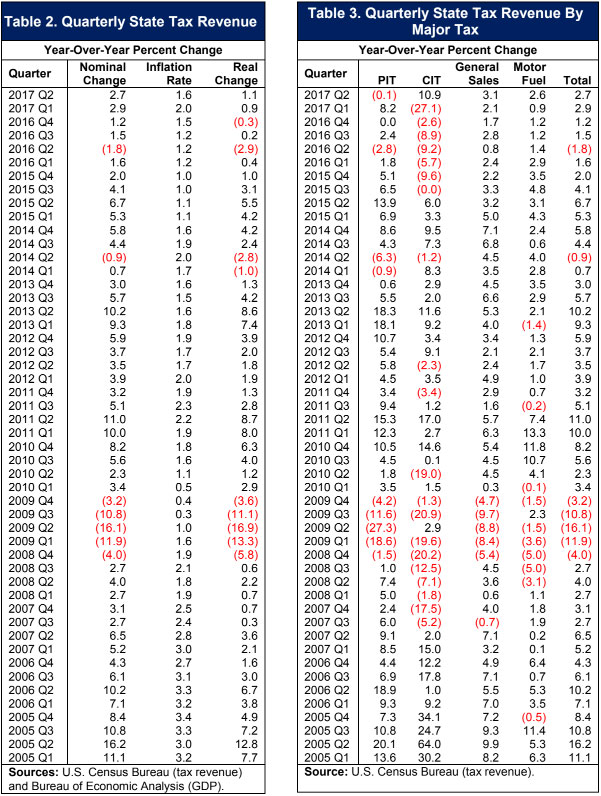

Note that this report often expresses quarterly changes as year-over-year percentages in the four-quarter moving average of tax revenues to smooth seasonal fluctuations in the quarterly data. Sometimes, especially when examining long-run trends as in Figure 1, we use inflation-adjusted data. At other times, such as when we examine short-run quarterly changes, we use nominal data. The text, figures, and tables indicate the data adjustments used. In previous “State Revenue Reports,” we suggested that recent fluctuations in state taxes were driven in part by volatility in the stock market and the federal fiscal cliff of 2013. 1 Major state taxes, adjusted for inflation, grew just 0.3 percent in the second quarter of 2017 (again, using the four-quarter moving average, compared to the same average in the second quarter of 2016). This weak growth follows three consecutive quarterly declines in state tax revenues.

Major local taxes grew 1.7 percent in the second quarter of 2017, using the same year-over-year measure of change in inflation-adjusted revenues.

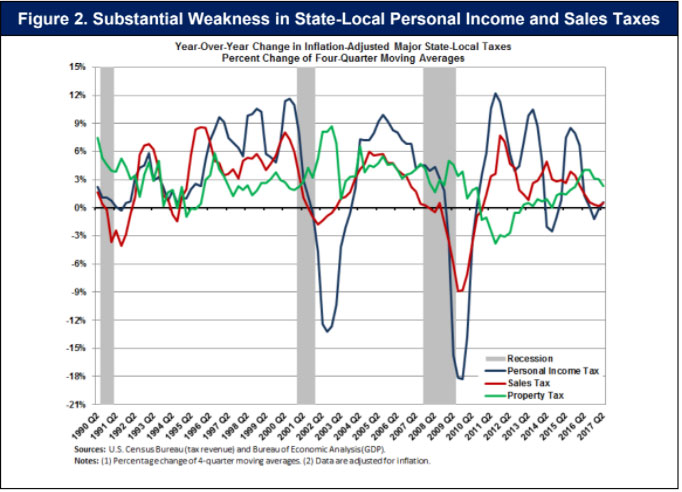

Figure 2 shows the year-over-year percent change in the moving four-quarter average of inflation-adjusted state and local income, sales, and property taxes. By this measure, state-local personal income and sales tax revenues weakened substantially in the last four quarters. Income tax collections (including both state and local collections) declined for two consecutive quarters yet resumed growth at 0.6 percent in the second quarter of 2017. State and local sales tax collections grew by a modest 0.5 percent in the second quarter of 2017. Property taxes, nearly all of which are collected by local governments, grew by 2.3 percent.

Total state government tax revenue grew 2.7 percent in the second quarter of 2017 relative to a year ago in nominal terms, according to Census Bureau data as adjusted by the Rockefeller Institute.2 State individual income tax collections fell 0.1 percent, while sales tax revenues increased by 3.1 percent and motor fuel tax collections grew by 2.6 percent. After seven consecutive quarterly declines, state corporate income tax revenues grew 10.9 percent. Table 2 shows changes in state tax revenues with and without adjustments for inflation, and Table 3 shows growth by major taxes in nominal terms.

Eleven states saw declines in total state tax collections in the second quarter of 2017 compared to the second quarter of 2016 (see the map in Figure 3A). This is a much smaller number of states reporting declines than even one year before, when 28 states experienced tax revenue reductions between the second quarters of 2015 and 2016 (Figure 3B). Nonetheless, the recent declines left several state budgets with holes to fix; eleven states had late budgets for fiscal year 2018, a record number.

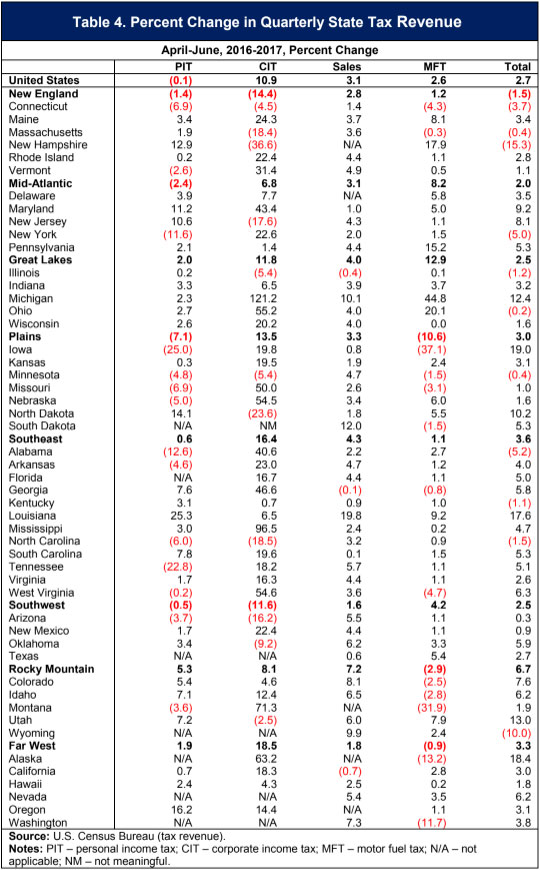

Total state tax revenues grew in all regions except New England in the second quarter of 2017 (see Table 4). The Rocky Mountain region recorded the strongest growth at 6.7 percent, while the Mid-Atlantic region reported weak growth at 2.0 percent. State tax revenues in New England fell 1.5 percent. Among individual states, New Hampshire and Wyoming reported the largest declines in total tax revenues at 15.3 and 10.0 percent, respectively. Oil and mineral dependent states rely heavily on severance taxes for state revenues. 4 Steep oil price declines throughout 2015 and early 2016 led to declines in severance tax collections and depressed economic activity, leading to weakness in other taxes. However, some of the oil and mineral dependent states reported growth in the second quarter of 2017, growth that comes after the depressed revenue levels of the previous two years. For example, total state tax revenues grew double digits in Alaska and Louisiana in the second quarter of 2017, at 18.4 and 17.6 percent, respectively. In Alaska, severance taxes constituted most of Alaska’s total tax revenue and remained less than half what they were four years ago. The growth in Louisiana was mostly attributable to legislative changes, including a one-percent increase in its sales tax and an increase in taxes on tobacco and alcohol.

Personal income tax revenues declined 0.1 percent in nominal terms and 1.7 percent in inflation-adjusted terms in the second quarter of 2017 compared to the same quarter in 2016. Personal income tax collections varied widely across the regions. The Rocky Mountain region saw the largest growth at 5.3 percent, while the Plains region reported the largest decline at 7.1 percent. Fourteen states reported declines in personal income tax collections. The largest drop was in Iowa at 25 percent, which was mostly attributable to large income tax refund payments issued in May. Refund payments were delayed in the previous months and accelerated in May.

We can get a clearer picture of collections from the personal income tax by breaking this source down into four components: withholding, quarterly estimated payments, final payments, and refunds. The Census Bureau does not collect data on individual components of personal income tax collections. The data presented here were collected by the Rockefeller Institute directly from the states (Table ). Our data are also more current than the Census Bureau data and provide a preliminary view of income tax collections for the third quarter of 2017.

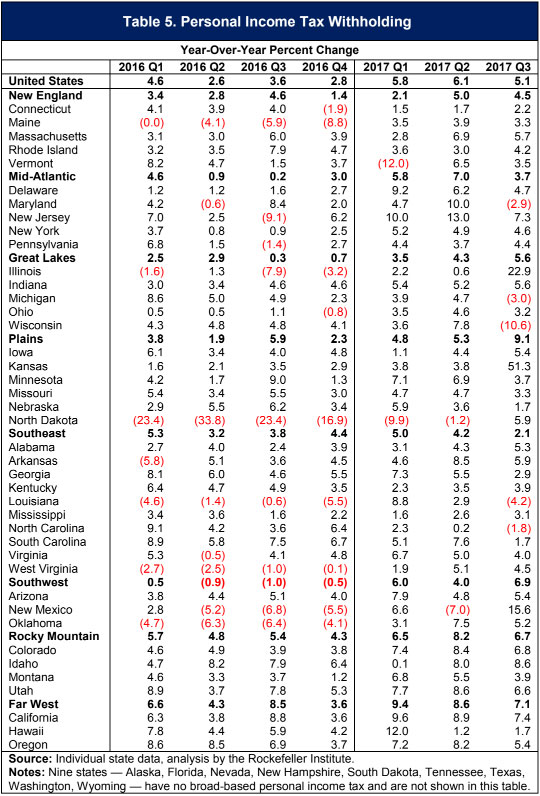

Withholding is a good indicator of the current strength of personal income tax revenue because it comes largely from current wages and is less volatile than estimated payments or final settlements. Table 5 shows state-by-state, year-over-year quarterly growth in withholding for the last seven quarters. Average quarterly growth in withholding was 3.4 percent in calendar year 2016. Growth in withholding then strengthened in calendar year 2017, when the first, second, and third quarters increased by 5.8, 6.1, and 5.1 percent, respectively. Growth in withholding was also widespread. Thirty-six states reported increases in withholding for the third quarter of 2017, while only five states reported declines. All regions showed growth; the Plains states reported the largest increase at 9.1 percent, while states in the Southeast saw the weakest growth at 2.1 percent.

Many high-income taxpayers make estimated tax payments (also known as declarations) on income not subject to withholding tax. This income often comes from investments, such as capital gains realized in the stock market. Estimated payments normally represent a small proportion of overall income-tax revenues; they can, however, exert a large impact on the direction of overall collections. Estimated payments accounted for 26 percent of total personal income tax revenues in the second quarter of 2017 but dropped to 16 percent of personal income tax revenues in the third quarter of 2017.

The first payment for each tax year is due in April in most states; the second, third, and fourth payments are generally due in June, September, and January (although many high-income taxpayers submit their last state income tax payment in December in order to deduct it on their federal tax return for that year). The first payment is difficult to interpret, as it can include a mix of payments related to both the current and previous tax years. The second and third payments are easier to interpret because they are more clearly related to the current tax year. However, payments can be “noisy” in that they reflect taxpayers’ responses to tax payment rules as well as expectations regarding future nonwage income.

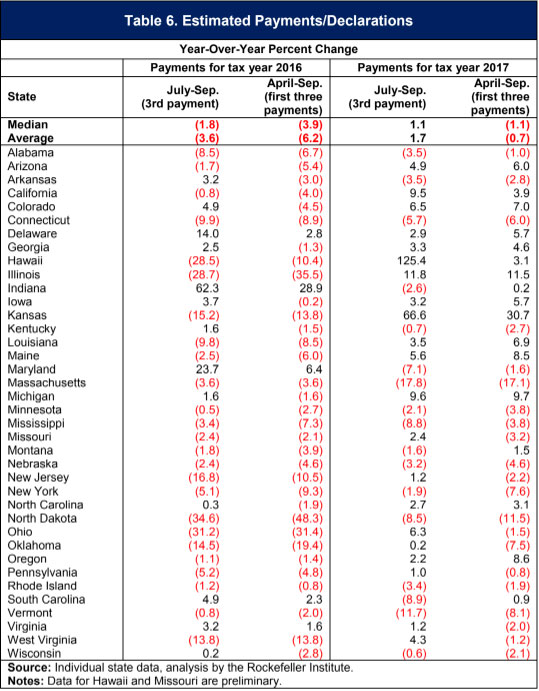

In the thirty-eight states for which we have data for the first, second, and third payments (mostly attributable to the 2017 tax year), the median third payment grew 1.1 percent. That growth contrasted with the 1.1 percent decline for the three 2017 payments combined (see Table 6). States varied substantially regarding changes in estimated payments. Seventeen states reported declines for the third payment, and twenty-one states reported declines for the first three payments combined.

Final tax payments normally represent a small share of total personal income tax revenues in the first, third, and fourth quarters of the tax year, and a much larger share in the second quarter of the tax year because of the April 15th income tax return deadline. Final payments accounted for 23 percent of all personal income tax revenues in the second quarter of 2017 but only 3 percent in the third quarter.

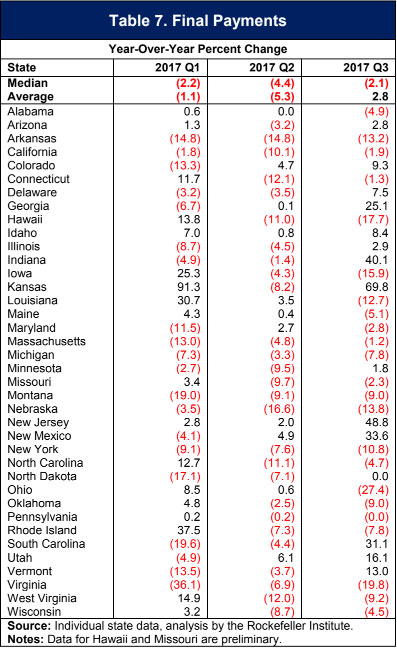

Table 2 shows that total final payments declined 5.3 percent in the critical second quarter of 2017. Table 7 shows state-level data for final payments. The median state reported consecutive declines in year-over-year quarterly growth in final payments for the first, second, and third quarters of 2017—declines of 2.2 percent in the first quarter of 2017, 4.4 percent in the second quarter, and 2.1 percent in the third.

Personal income tax refunds grew 9.4 and 9.1 percent, respectively, in the second and third quarters of 2017 compared to the same quarters in 2016. States paid out about $2.0 billion more in refunds in the second quarter of 2017 and about $0.4 billion more in the third quarter. Twenty-three states paid out more refunds in the second quarter of 2017 compared to the same quarter of 2016, and nineteen states paid out more refunds in the third quarter of 2017. New York and California alone paid out $1.1 billion and $0.6 billion more refunds in the second quarter of 2017. The large refunds in New York are attributable to timing issues; the state paid out $1.4 billion less in the first quarter of 2017 compared to the same period in 2016.

General state sales tax collections grew 3.1 percent in second quarter of 2017 from the same period in 2016. Inflation-adjusted growth was 1.5 percent. Sales tax collections have grown continuously since the first quarter of 2010, averaging 3.8 percent in quarterly growth in nominal terms. However, the growth slowed in calendar year 2016 and the first two quarters of 2017, when average quarterly growth was 2.1 percent.

Sales tax collections increased in all regions. The Rocky Mountain region reported the largest growth at 7.2 percent, while the Southwest region saw the weakest growth at 1.6 percent. Forty-two states reported growth in sales tax collections in the second quarter of 2017. Only three states – California, Georgia, and Illinois – reported declines.

Corporate income tax revenue is highly variable because of volatility in corporate profits and the timing of tax payments. Many states collect little revenue from corporate taxes and can experience large fluctuations in percentage terms with little budgetary impact.

After seven consecutive quarterly declines, corporate income tax revenue grew 10.9 percent in the second quarter of 2017 compared to a year earlier. However, the growth is largely attributable to a timing issue. The Internal Revenue Service changed the income tax return filing due date for returns and final payments from March 15th to April 15th for C-corporations, which is partially the cause of steep declines in corporate income tax returns in the first quarter of 2017 and strong growth in the second quarter of 2017.

Motor fuel sales tax collections in the second quarter of 2017 increased by 2.6 percent from the same period in 2016. Motor fuel sales tax collections have fluctuated in the post-Great Recession period. Economic growth, changing gas prices, general increases in the fuel-efficiency of vehicles, and changing driving habits of Americans all affect gasoline consumption and motor fuel taxes. Changes in state motor fuel rates also affect tax collections. Large disparities exist among states and regions. Motor fuel sales tax collections fell among the Plains, Rocky Mountain, and Far West states and grew elsewhere. The largest decline was in the Plains region at 10.6 percent, while the largest growth occurred among Great Lakes states at 12.9 percent in the second quarter of 2017. Thirteen states reported declines in motor fuel sales tax collections in the second quarter of 2017.

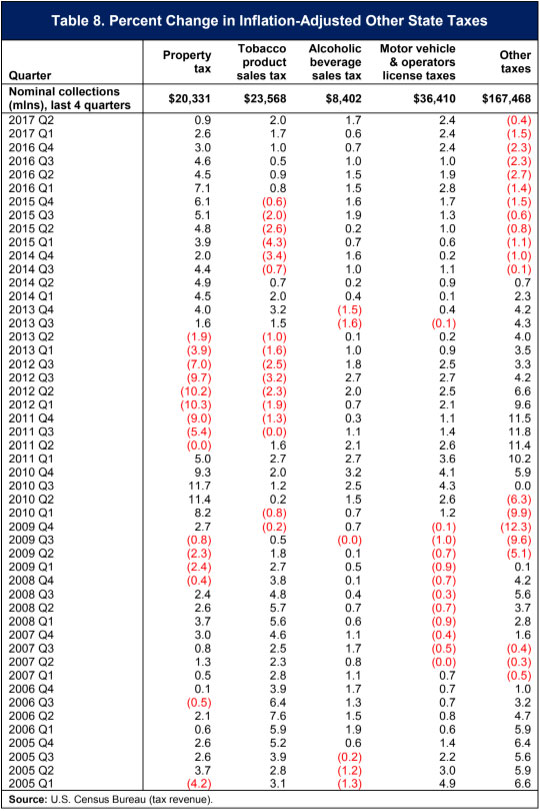

Census Bureau quarterly data on state tax collections provide detailed information for some of the smaller taxes. In Table 8, we show growth rates for these taxes, by collecting year-over-year growth rates of the four-quarter average of inflation-adjusted revenue for the nation as a whole. In the second quarter of 2017, states collected $55.8 billion from smaller tax sources, which comprised 20 percent of total state tax collections. Revenues from smaller tax sources showed a mixed picture in the second quarter of 2017.

Inflation-adjusted state property taxes increased by 0.9 percent. After six consecutive quarterly declines, collections from tobacco product sales resumed growth in 2016, mostly due to tax rate increases in several states. Tax revenues from alcoholic beverage sales and from motor vehicle and operators’ licenses grew at rates of 1.7 and 2.4 percent, respectively, in the second quarter of 2017. Revenues from all other smaller tax sources declined 0.4 percent.

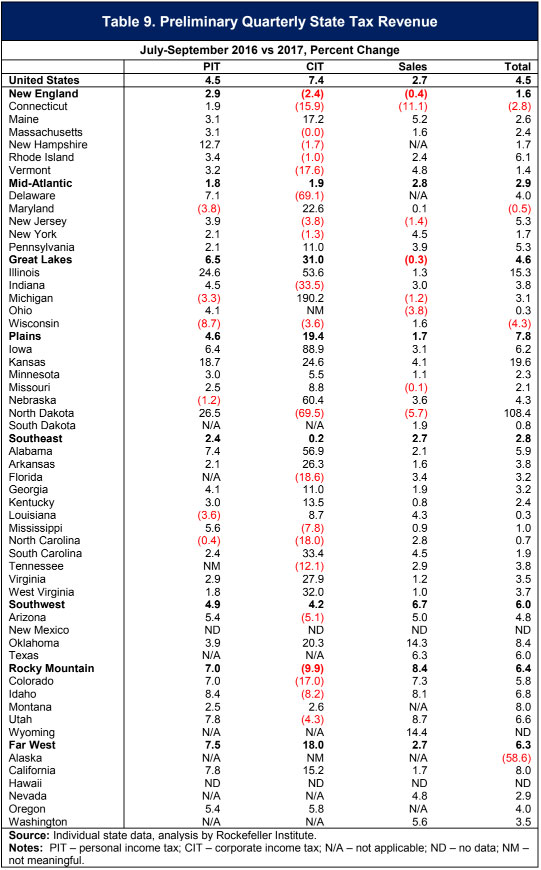

Preliminary figures collected by the Rockefeller Institute for the July-September quarter of 2017 showed stronger growth in overall state tax collections, as well as in personal income and sales tax collections. Total tax collections increased by 4.5 percent in the third quarter compared to the same quarter in 2016. Personal income tax collections grew 4.5 percent and sales tax collections increased 2.7 percent. Growth was also observed in corporate income tax collections at 7.4 percent. Table 9 shows state-by-state changes in major tax revenues for the third quarter of 2017 compared to the same quarter of 2016. According to preliminary data, forty-three states saw growth in overall state tax revenue collections.

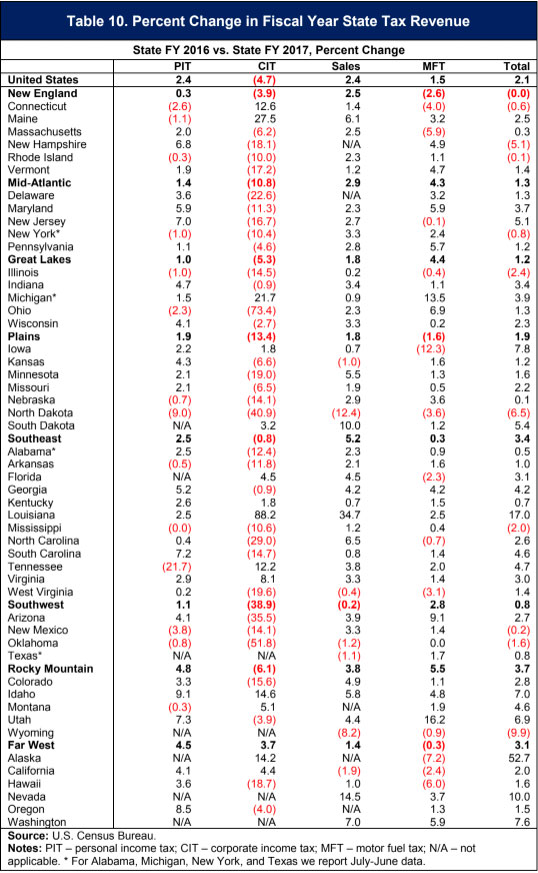

The Census Bureau has not yet reported annual state tax revenue for fiscal year 2017, which ended in June for 46 states, but we constructed estimates using quarterly data. According to these data, states collected $949 billion in total tax revenues in fiscal year 2017, a gain of 2.1 percent from the $929 billion collected in fiscal year 2016 (see Table 10). The personal income tax and sales tax grew 2.4 percent each, while the corporate income tax declined 4.7 percent. State motor fuel sales tax collections grew 1.5 percent.

Revenue collections grew in all regions but New England. The strongest growth was in the Rocky Mountain region at 3.7 percent; the weakest growth was in the Southwest at 0.8 percent. Forty states reported growth in fiscal 2017 compared to fiscal 2016, while ten states reported declines. The largest declines were in Wyoming and North Dakota, at 9.9 and 6.5 percent, respectively. Declines in both states are partially attributable to their reliance on severance taxes, which were eroded by falling oil prices. Thirty-eight of forty-five states with broad-based sales tax collections reported growth in sales tax collections, while seven states reported declines. Twenty-nine states reported growth in personal income tax collections while fourteen states reported declines.

Although state government tax revenues grew in the second quarter of 2017, and revenue increases were widespread among the states, growth was weak and mixed across different revenue sources. Sales taxes increased consistently but lagged behind growth rates in previous economic expansions. Personal income taxes continued to be volatile and uncertain; they declined in the second quarter after a short-lived increase in the first. Corporate income taxes resumed growth in the second quarter of 2017 but probably due to an IRS change in filing deadlines; the prior persistent declines in the corporate income tax may well return. Local government tax revenues also increased in the second quarter. Again, however, the growth was weak and varied across different taxes, with most of the growth coming from steady yet small increases in property tax revenues.

Taken together, state and local combined tax revenues grew in the second quarter of 2017 but at a rate slower than in recent quarters, despite the continued and fairly robust economic recovery. Perhaps the third and later quarters will check this slowdown. But if the recent weak and uncertain revenue trends continue, state and local governments may face difficult fiscal conditions, perhaps to be exacerbated by federal tax changes, federal budget cuts in domestic spending (including federal assistance), and changes in healthcare policy that increase the number of uninsured individuals.