It’s no secret that upstate, rural communities like Sullivan County have been hit especially hard by the opioid epidemic, even though the phenomenon is by no means confined to these areas. In 2016, fourteen deaths were attributed to opioid abuse in Sullivan County, and the problem is continuing to grow. According to early estimates for 2017, as many as twenty-seven residents died of a drug overdose in the county last year.

Although no one is sure exactly how to solve the opioid problem in Sullivan County, doing nothing is not an option. What the response looks like, however, depends on whom you ask and where they work. To get a better feel for what the local fight against opioids looks like, we spoke to a range of people in Sullivan County about their experiences. What came into focus was a multifront battle fought along the lines of crisis management, treatment and recovery, and prevention.

Crisis Management

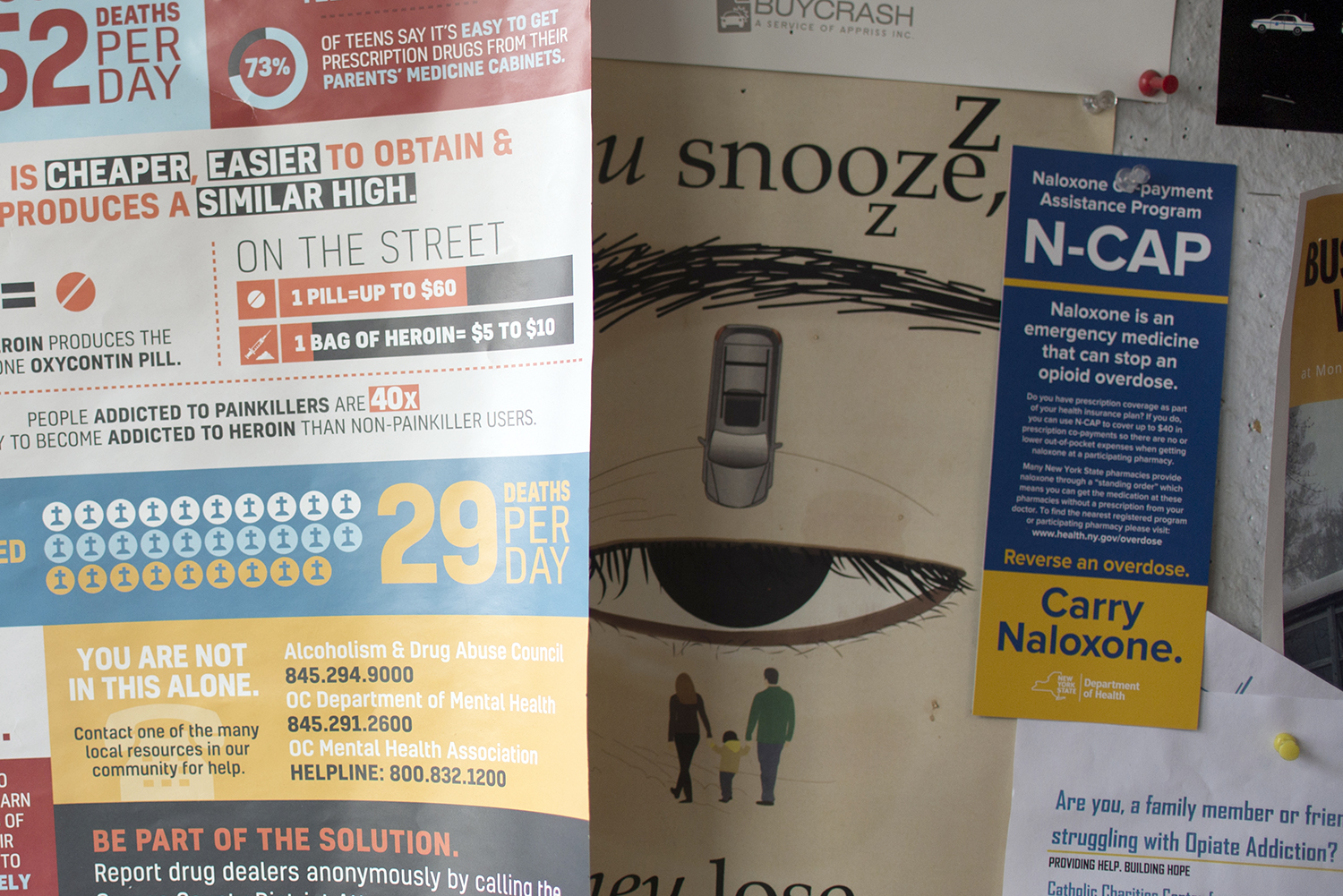

Upon recognizing an extensive need for resources and awareness, community organizers and public officials sponsored Narcan trainings throughout Sullivan and Orange Counties.

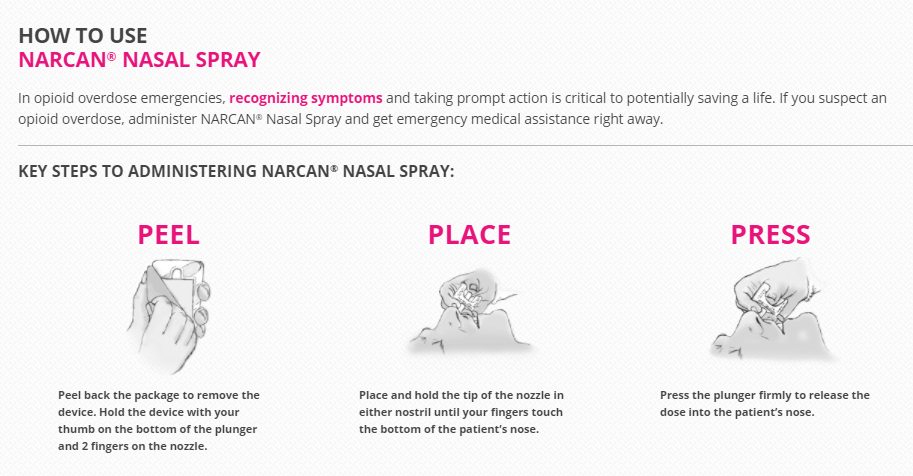

Narcan, which is a medication used to reverse opioid overdose, “is a prefilled, needle-free device that requires no assembly and is sprayed into one nostril while patients lay on their back.” Between January and December 2017, the Sullivan County Public Health Department trained 246 people to dispense Narcan, Catholic Charities an additional 244, and the Greater Pine Bush Partnership another 300. It’s amazing, one organizer told us, how many lives a single training can save.

Sullivan County Narcan Trainings by Specialty Area, 2017

| Initial Law Enforcement | 26 |

| Refresher Law Enforcement | 48 |

| Firefighters | 65 |

| School Personnel and Students | 29 |

| County Employees | 11 |

| Nursing and Medical Professionals | 11 |

| EMS Providers | 37 |

| 911 Call Center workers | 18 |

| County Commissioner Refresher | 1 |

| 2017 Total Trained by Sullivan County Public Health | 246 |

But not everyone is as enthusiastic about administering Narcan in this way. In fact, we heard about growing frustration among first responders who are concerned that Narcan doesn’t just save lives, it also enables an addiction. Indeed, it is not uncommon for police officers, EMS workers, and family members to revive the same person multiple times — even in the same day. In response to the argument that Narcan offers little more than a safety net for risky behavior, one public health administrator pointed out during a meeting of the Opioid Epidemic Task Force that, although the county can’t mandate substance abuse treatment, people at least need to be alive to get there. From this perspective, Narcan gives public health professionals another chance to intervene, and people struggling with addiction another chance to seek treatment.

Top: A bulletin board at the Monticello Police Department in Monticello.

Bottom: Instructions for using Narcan from www.narcan.com.

A second, yet related, approach to crisis management in Sullivan seeks to cut off immediate access to opioids in the county by removing drugs from people’s homes. The Prescription Drug Abuse Prevention Task Force thus organizes Take Back Days in partnership with the local Sheriff’s Office. According to Public Health Director Nancy McGraw, the purpose of these events is to prevent prescription drugs from “falling into the wrong hands and being abused or sold on the streets.”

On any given Take Back Day, people with unwanted pills can drop them off at a temporary collection site, no questions asked, and the Sheriff’s Office will transport them to Poughkeepsie for incineration. The county hopes to obtain its own incinerator soon so transport to Poughkeepsie becomes unnecessary. In addition to numerous Take Back Days sponsored throughout the year, permanent drop boxes have been installed at the following local police stations: Liberty, Fallsburg and Monticello, as well as the lobby of the Department of Family Services building. As a result of these combined efforts, more than 1,700 pounds of unwanted medication have been removed from Sullivan County.

For its part, the Sullivan County Sheriff’s office has made a concerted effort to identify and arrest the leaders of major drug trafficking organizations. In 2014, for example, as a result of two teenage overdose deaths in Livingston Manor, Sullivan County Sheriff Michael Schiff launched an investigation into the drug’s supplier. In less than a year, a partnership between the Sullivan County Sheriff’s office, the New York City Police Department, and multiple federal agencies led to the arrests of five members of a Bronx-based drug trafficking network and the seizure of nearly $5 million (twenty-six pounds) of heroin. In addition to takedowns and investigations, the county is considering adopting a program like Wallkill Cares, which allows people in the neighboring town of Wallkill to request treatment for substance abuse from the police in Orange County.

Although county-level officials and organizers are coming together to combat opioids in any way possible, many people believe that the problem is only getting worse. Indeed, with so much time and energy being invested in crisis management, some of the more expensive solutions, like medical treatment and prevention, seem even further out of reach. “It’s like treating someone for a burn when they’re still in the fire,” one public health administrator told us — we’re “treating the problem upside-down.”

A safe drop box in the Monticello Police Department. Right: Sullivan County Public Health Director Nancy McGraw in her office in Liberty, New York.

Treatment and Recovery

Ironically, in a place overrun by vacant rooms and abandoned beds, remnants of the luxurious hotels, bungalow colonies, and boarding rooms of the past, one of the greatest challenges facing Sullivan County is limited access to drug treatment facilities and housing. Although two hotels — Paul’s Hotel in Swan Lake and the Grand Hotel in Parksville (Brown 2002) — were purchased and converted into adult residential facilities by Samaritan Daytop Village, both were closed in the early 2010s after the comprehensive human services organization filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy (Sparks 2014). The Daytop facilities were generally reserved for New York City patients; still, it is difficult to comprehend why the number of drug treatment facilities would decline as the number of opioid deaths skyrocketed.

Sullivan County is not alone in watching its long-term treatment facilities close down. As the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration observed, long-term residential treatment, which can have lengths of stay anywhere from twelve to eighteen months, is “relatively uncommon.” Quite frankly, some people in the community are convinced that long-term care is rare because it’s exorbitantly expensive. “If we’re really committed then why aren’t people getting services,” exclaimed one frustrated member of the Sullivan County Opioid Epidemic Task Force at a recent meeting. “Why aren’t we paying for it?!”

With so much time and energy being invested in crisis management, some of the more expensive solutions, like medical treatment and prevention, seem even further out of reach. “It’s like treating someone for a burn when they’re still in the fire,” one public health administrator told us.

Still, people in the public health community offer an alternative explanation, which is that the model of care has changed. While putting a person in long-term treatment might help them achieve sobriety, it does not always equip them with the tools they need to successfully navigate challenges at home. “Long-term treatment programs closed because they weren’t successful,” one public health administrator said, though not everybody agrees.

For people seeking treatment in Sullivan County, one option available to them is Catholic Charities, a comprehensive human services organization with a chemical dependency clinic in Monticello, in the heart of Sullivan County. In addition to providing medically supervised detox and withdrawal programs, Catholic Charities offers intensive day rehabilitation services; residential programming for men and women; and community-based supportive housing apartments. Surprisingly, the detox center at the public hospital closed a few years ago. “They were never at full census,” explained one public health administrator, after the hospital changed its admission criteria to include physical withdrawal. “If you’ve ever encountered an addict, they are not going to let themselves go through physical withdrawal because it’s so uncomfortable, especially for opiates, it’s unbearable…. So their census began to deplete, and it wasn’t cost effective. It’s very high cost to run a detox center in a hospital.”

Catholic Charities chemical dependency clinic in Monticello.

For those on the other side of treatment, the process of recovery begins. According to one public health administrator, more needs to be done to prevent people from relapsing in recovery. Drawing a comparison between the safe environment of a long-term treatment facility and the challenges people face back home, she expressed frustration over her inability to mandate patient participation in Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), which was deemed a “religious activity” by the federal Court of Appeals. “We can’t mandate AA/NA [Narcotics Anonymous] which is driving me crazy, because of the legality,” she explained:

I think the field actually lost it when they stated that AA/NA was a religious affiliation and that we couldn’t make people go, ‘cause we were more successful when they had that buffer, if that makes sense, they had a safety net. Now they have to find it on their own. We can suggest it. Some people still do it. The majority of them don’t, you know . . . So without being able to mandate some kind of buffer to help them and support them through the process while they are out there, I think a lot of them trip and fall.

Instead of mandating participation in Narcotics Anonymous, public health administrators can connect individuals to a licensed peer recovery coach. In addition to developing a recovery plan, these coaches assist clients by putting them in touch with a wide variety of services and acting as a personal guide and mentor. The program, known as Friends for Recovery, circumvents some of the bureaucratic red tape found in hospitals. “HIPAA [the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act] impairs self-help groups,” one peer recovery coach told us. “It squashes the intimacy between recovering addicts.” By comparison, Friends of Recovery, which emphasizes holistic healing and other spiritual principles, creates a place where people can talk openly about their problems and build fellowship.

In addition to peer recovery coaches, the county is working with local organizations to start a support group for those who lost loved ones to overdose.

Prevention

In light of the growing death rate, people in Sullivan County recognize the need for something more than just treatment. “We need treatment, we absolutely need it,” one provider explained. “But the word treatment is what it is — it’s treatment. It’s not a cure. Prevention is a cure. It’s an absolute cure.”

Growing recognition of the need to stop drug addiction before it starts has led to a range of responses directed at prevention. Hindering these efforts, however, is a lack of resources. Although treatment in Sullivan County remains vastly underfunded, there are even fewer dollars earmarked for prevention. The State Targeted Response (STR) grant awarded to Catholic Charities is a perfect example of this disparity in funding. In September 2017, Governor Andrew Cuomo announced that Catholic Charities Community Services of Orange and Sullivan would receive a $2 million grant to enhance access to prevention, treatment, and recovery services. However, little more than a $100,000 was set aside to deliver an afterschool, evidence-based prevention program known as Too Good for Drugs. Although the program seeks “to promote life skills” and “resistance to the use of illegal drugs,” schools have difficulty freeing up staff for trainings and integrating the program into an already cramped curriculum.

Top: A notice for an addiction hotline in a diner in Monticello.

Left: The Tri-County Community Partnership’s “Have a Slice” campaign.

In the absence of money, community organizers have done what they can to raise awareness. In February 2017, the Tri-County Community Partnership (formerly the Greater Pine Bush Partnership) launched its “Have a Slice” campaign to encourage parents to talk to their kids about drugs. Eight pizzerias participated, placing stickers on pizza boxes with facts about drug use that could be used as conversation starters. Numerous panel discussions and events have also been held to educate the community about drug and alcohol abuse. In October 2017, the Sullivan County Drug Abuse Task Force sponsored a public health conference at Bethel Woods entitled “Local Solutions to a National Opioid Crisis.” In addition to covering such topics as the “biology of substance use disorders” and “medication assisted treatment,” elected officials, public health experts, and law enforcement officials discussed ways of working together to end the opioid problem. In a community strapped for cash, something as simple as a conversation can go a long way.

Conclusion

The fight against opioids in Sullivan County is carried out not only in police stations and hospitals but around the kitchen table. Although many people expressed concern that the opioid problem is growing, the inability to contain the spread of opioids has less to do with a lack of resolve in the county than a lack of resources. Even though a permanent solution remains elusive, folks in Sullivan County continue to hold the frontline.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Katie Zuber is the assistant director for policy and research at the Rockefeller Institute of Government

Patricia Strach is the deputy director for research at the Rockefeller Institute of Government

SUGGESTED CITATION

Katie Zuber et al., “Fighting Back,” Rockefeller Institute of Government, March 28, 2018, https://rockinst.org/blog/stories-sullivan-fighting-back/.

READ THE SERIES

The Rockefeller Institute’s Stories from Sullivan series combines aggregate data analysis with on-the-ground research in affected communities to provide insight into what the opioid problem looks like, how communities respond, and what kinds of policies have the best chances of making a difference. Follow along here and on social media with the hashtag #StoriesfromSullivan.