Earlier this year, both New York and New Jersey looked like they were poised to pass adult-use marijuana legislation. Now the future of adult-use marijuana in both states is in doubt; New Jersey has postponed considering the issue until 2020 and time is running out for New York’s current legislative session. Historically, adult-use marijuana in the states has generally been passed through voter initiative. Of the 10 states that permit adult-use marijuana, only Vermont did so through the legislative process — permitting home cultivation of a small number of marijuana plants, but failing to tackle the more complex issue of creating a commercial market for retail sales. The other nine states have implemented adult-use through the initiative process, which allows citizens to propose a new statute to be approved directly by voters and circumvent the legislature. Why have efforts to pass adult-use marijuana stalled legislatively while they have achieved better success through ballot measures?

One factor that may help explain the difficulty in passing adult-use legislation through the more traditional legislative process is the role of interest groups. Political scientist E.E. Schattschneider discussed the scope of conflict in his seminal work The Semisovereign People: A Realist’s View of Democracy in America — those that are losing a conflict want to widen the audience for the discussion in order to garner additional support for their cause. Interest groups, however, benefit from keeping the scope of conflict narrow. When an issue is being decided by a legislature, the primary players are much easier to identify and attempt to influence — the lawmakers responsible for drafting and supporting a piece of legislation. When fewer people need to be persuaded, it is easier to tailor the message to the individual member and their concerns. When the scope of the conflict widens with the use of initiative and a majority of an electorate now has to be convinced, this challenge increases. This is not to say that interest groups don’t have an impact in the initiative process — they are often instrumental in getting issues on the ballot to begin with — but there are more variables that must be considered with a more diverse and less predictable audience, and tactics and messaging must change.

The legislative process also forces elected officials to take responsibility for their vote, which may be daunting given that there are so many unknowns associated with the impact of marijuana.

The legislative process also forces elected officials to take responsibility for their vote, which may be daunting given that there are so many unknowns associated with the impact of marijuana. Because federal prohibition has made marijuana difficult to study, there is not a clear body of evidence on how long-term marijuana usage affects the body. The data from states that have legalized adult use on societal concerns, like marijuana-related traffic accidents and youth consumption, have been somewhat anecdotal and hard to draw conclusions from given the limited timeframe of implementation. This lack of information may contribute to some legislators being hesitant to provide an affirmative vote on adult-use marijuana — without a clear picture of the consequences of legalization, the risk may outweigh the reward.

Creating a state adult-use program in the shadow of federal constraints and a potential crackdown may also contribute to the legislative gridlock. There are extra hurdles and complexities associated with implementing marijuana policy that other legislation doesn’t have to address. And, while marijuana legalization enjoys popular support, it is not clear that implementing marijuana policy is an important factor in determining a candidate’s reelection success. In fact, with many counties and cities leaning toward opting out of a statewide adult-use marijuana program, some legislators have an incentive to not support a bill.

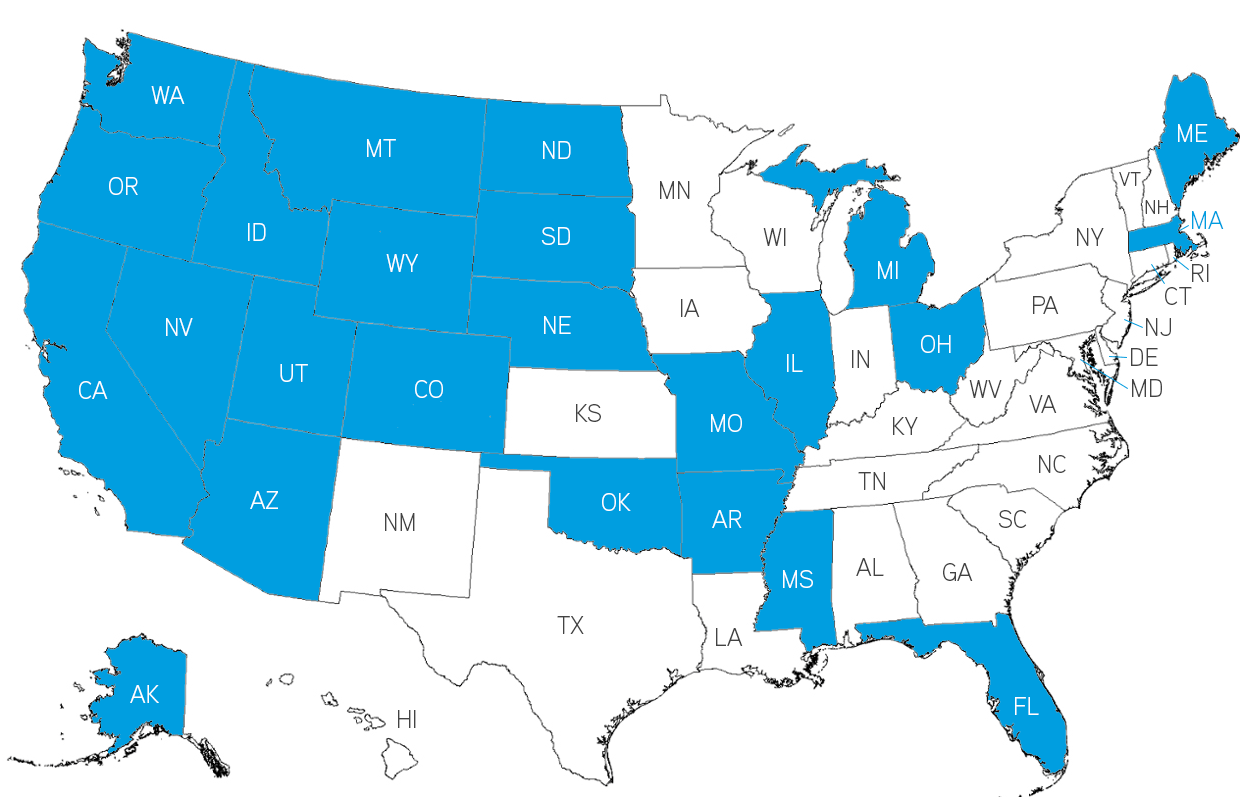

States with Initiative

SOURCE: “Initiative and Referendum States,” National Conference of State Legislatures, accessed May 23, 2019, http://www.ncsl.org/research/elections-and-campaigns/chart-of-the-initiative-states.aspx.

Voters are more likely to turn to the initiative process when they are frustrated by the inactivity of the legislature on issues that enjoy popular, often bipartisan support among the electorate, or when the voters have overall lost trust in their state elected officials. The initiative process takes the legislature out of the lawmaking process, allowing citizens to directly decide whether a statute should be approved. In theory, once an initiative passes, lawmakers are forced to then implement the will of the voters; it’s a way to force an issue on the agenda that lawmakers are either ignoring or are unable to come to a consensus on for legislation. South Dakota became the first state to implement the initiative in 1898 and currently 24 states have some form of the initiative on the books. The initiative process varies from state to state in the requirements but, generally, citizens are able to get proposed legislation or a constitutional amendment on the ballot if they meet the state’s predetermined signatory requirements. The use of initiatives in the United States has fluctuated over time, with spikes in its usage in 1910-19, 1930-39, and 1990-2009. There has also been a recent uptick in state initiatives on the ballot in 2016 and 2018. This recent upturn may be correlated with the increased number of states that have unified party control of both the governorship and the legislature. As of 2019, 36 state governments — comprising 76 percent of the US population — are controlled by one party. For an issue like marijuana policy, where public opinion has shifted more quickly than that of most legislators, the states that have an initiative process can be more responsive than a state that doesn’t permit an end-run around the normal legislative process.

Trends in Initiatives Introduced and Percent Passed, 1990-2018

| YEAR | INITIATIVES IN STATES | PERCENT PASSED |

| 2018 | 60 | 46.7% |

| 2016 | 72 | 65.3% |

| 2014 | 35 | 42.9% |

| 2012 | 42 | 42.9% |

| 2010 | 42 | 45.2% |

| 2008 | 59 | 42.3% |

| 2006 | 76 | 39.5% |

| 2004 | 59 | 55.9% |

| 2002 | 49 | 42.9% |

| 2000 | 69 | 44.9% |

| 1998 | 55 | 63.6% |

| 1996 | 87 | 48.3% |

| 1994 | 68 | 50% |

| 1992 | 62 | 50% |

| 1990 | 57 | 29.8% |

SOURCE: “Statewide Ballot Measures Database,” National Conference of State Legislatures, accessed May 23, 2019, http://www.ncsl.org/research/elections-and-campaigns/ballot-measures-database.aspx.

Voters are more likely to turn to the initiative process when they are frustrated by the inactivity of the legislature on issues that enjoy popular, often bipartisan support among the electorate, or when the voters have overall lost trust in their state elected officials.

This is not to say that the initiative process is perfect or that legislative action on adult-use marijuana policy will always be the exception to the rule. While the initiative process may be a quicker way to enact adult-use marijuana in the short run, it often involves amending part of the state constitution, which can make it harder for changes to be made to legislation in the long run. State legislatures have moved to minimize the impact of voter-passed initiatives — in 2018, for example, voters in Florida passed a constitutional amendment via initiative that would restore voting rights to some felons after they had completed their sentences. The Florida legislature, however, passed additional restrictions on the restoration of the vote, including requiring felons to pay back fines and court fees. Some state Medicaid expansion initiatives have been limited. Eleven states currently have no restrictions on legislative alteration, permitting lawmakers to repeal or amend statutes passed by initiative. Of the 97 state initiatives that were passed from 2010-18, 28 were altered by legislatures, with Maine (4/8), Colorado (3/5), and Oregon (3/5) being the worst offenders. Marijuana policy initiatives were subject to the most legislative action: eight of the 28 instances (28.6 percent) of legislative alteration in this time period impact marijuana initiatives passed by voters. Many states are also considering legislation to make the initiative process more difficult; in 2018, 203 bills governing ballot measures were introduced in 34 states. In total, 201 bills governing ballot measures have been introduced in 30 states as of April 2019. State legislatures, it appears, don’t enjoy being left out of the legislative process.

Where does that leave marijuana policy? Public support for marijuana legalization does not show signs of slowing down and though addressing adult-use marijuana through legislation is harder, it’s not impossible. Eventually one state legislature will crack the code for passing adult-use marijuana, and that can serve as a roadmap for other states that either don’t have the initiative process or where using the initiative process is no longer a viable alternative due to increased restrictions.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Heather Trela is chief of staff and fellow at the Rockefeller Institute of Government

READ THE SERIES

POLICYMAKERS CONSIDERING ADULT-USE MARIJUANA LEGALIZATION ARE NOT DOING SO IN A VACUUM. To date, 10 states and the District of Columbia have already been down this path. Their experiences implementing new laws can serve as a potential roadmap for other states considering legalization. To paraphrase U.S. Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis, states can serve as “laboratories of democracy” that can inform legislation in other states. Read the series.